Simultaneous cycle and fluid optimisation for ORC systems

For those in academia the summer months generally provides the opportunity to focus on getting some research done, alongside maybe a holiday. Anyway, with this in mind I thought this month it would be great to shine a spotlight on some my recently published research looking at a new method to identify optimal ORC systems.

Hopefully, from the ORC-101 section the concepts of an organic Rankine cycle (ORC) and a working fluid are becoming familiar to you, if they are not already. Well, when you start to think about ORC systems, one of the main questions that arises is “which fluid is the best for a particular application?”. The number of fluids that could be considered is vast, and to some extent depends on how exotic you want to go. For example, a large number of studies out there compare somewhere in the region 10 to 30 different fluids, while other studies consider as many as 3000. So, how do I find the best one for my application?

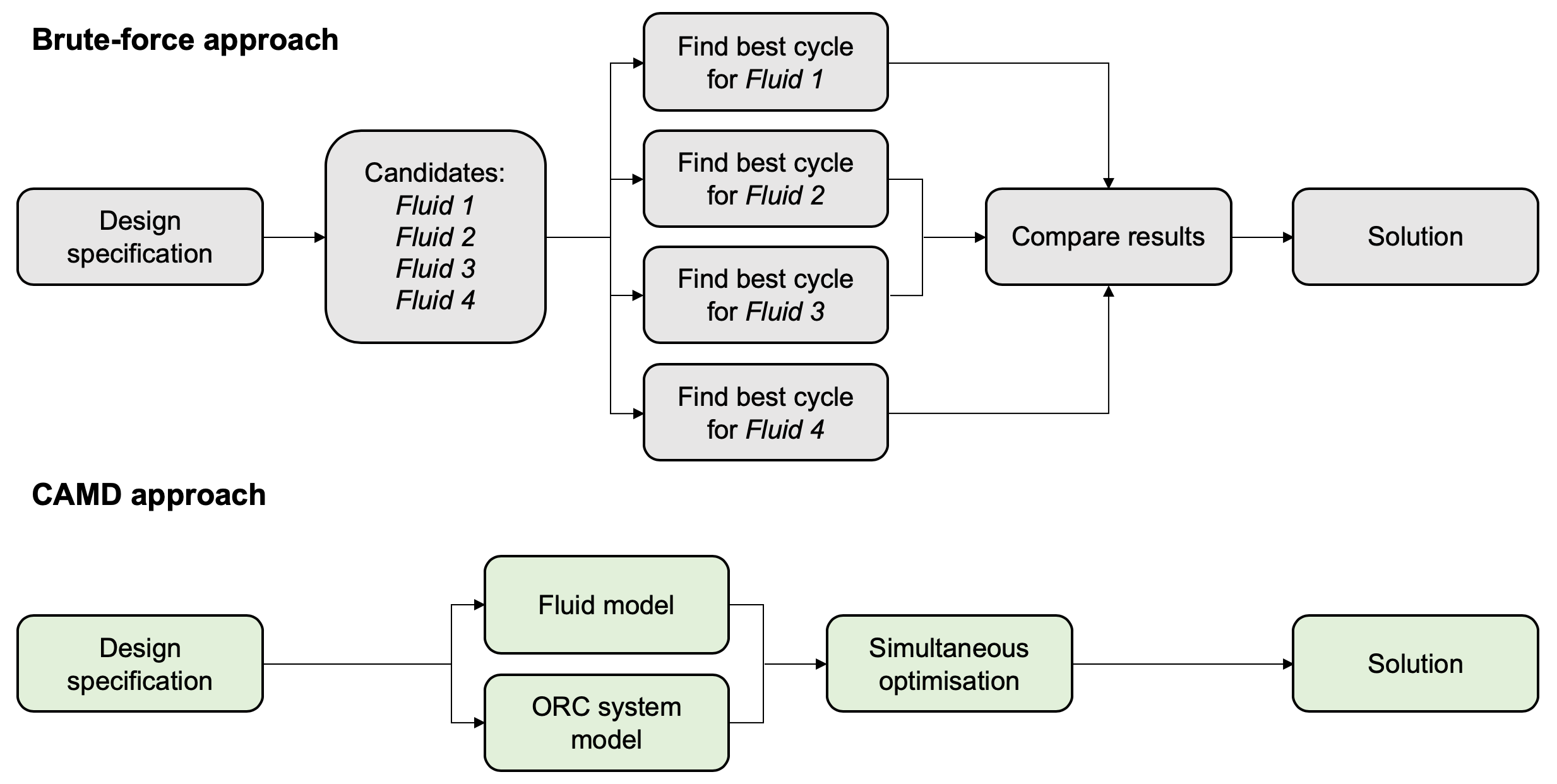

The most common approach to finding an optimal fluid for a particular application relies on a brute-force approach. That is to say that the performance of an ORC system is evaluated (using computational models of the system) for every fluid under consideration and the fluid with the best performance is selected. Of course, such a method will generally work, but it requires a lot of effort (mainly from the computer) and may also take some time to consider all possible fluids. Moreover, depending on how many fluids you originally start with, this method might not necessarily result in the best solution. For example, what if the optimal fluid wasn’t in my original group of fluids to start with? It therefore needs to rely on some sort of preliminary screening to get the initial group of fluids, which is likely to be subjective.

Thus, in the interest of saving time and effort, recent research has sought out a more holistic approach to the process of selecting the best fluid for a particular application. One way of doing this is to employ a process called computer-aided molecular design, or CAMD, which allows the chemical structure of the fluid to be designed at the same time as the ORC system is simulated. As part of my current research, I have borrowed some of the ideas from CAMD and developed a computer model that can simultaneously identify the ideal characteristics of the fluid and the ORC system, thus removing the need for the brute-force approach.

Central to the approach is the use of the Peng-Robinson equation of state. An equation of state is essentially a mathematical description of a fluid that can be used to describe how a fluid behaves as it undergoes changes in its operating conditions (e.g., a change in temperature or pressure). To model a particular fluid, the equation of state requires, as inputs, a number of fluid-specific parameters, which are generally derived from experiments. Thus, any possible fluid can be modelled by knowing the correct values for these parameters and then feeding these into the equation of state.

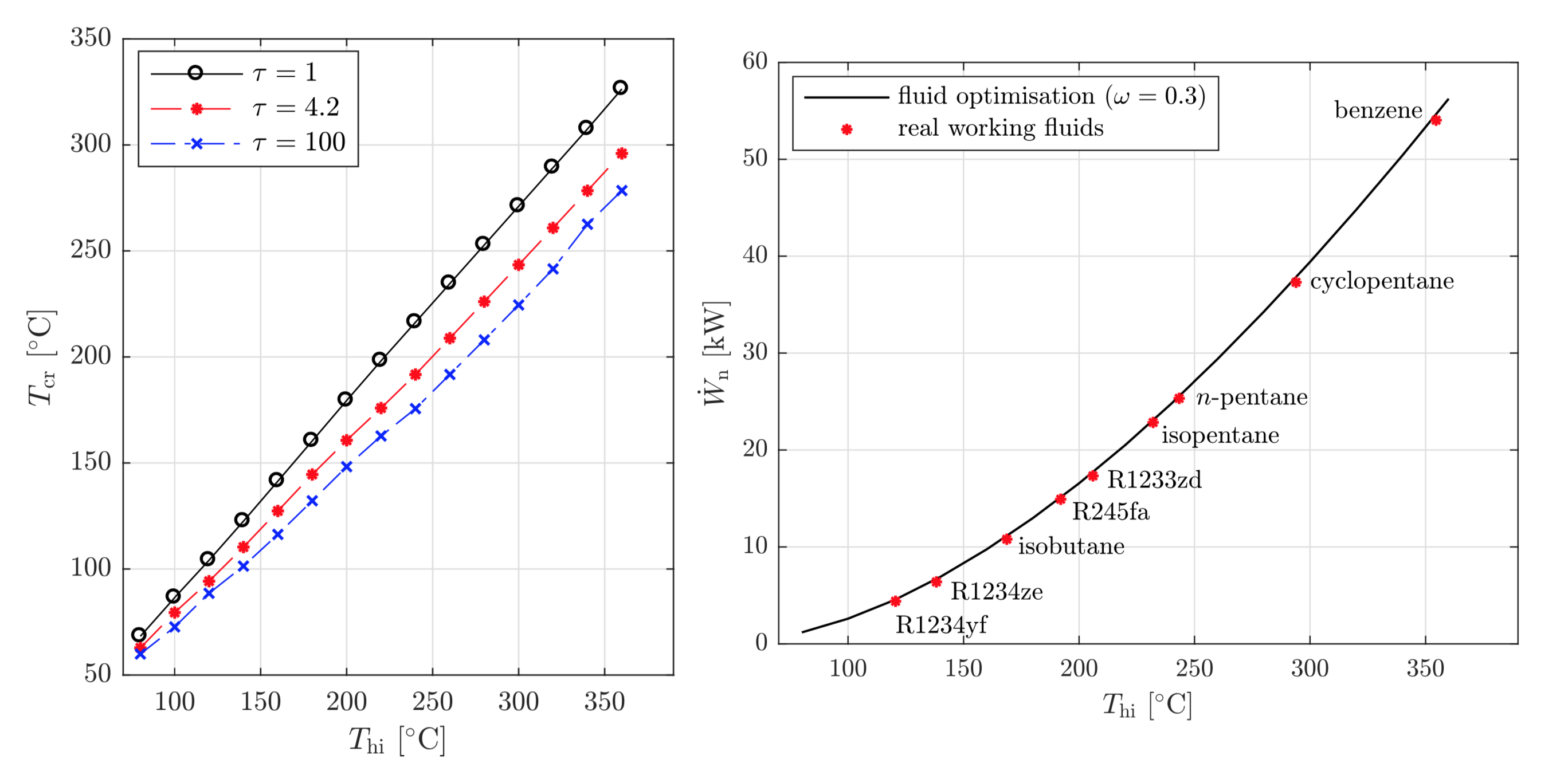

The model developed in my research works by considering these fluid parameters as variables that can change during the computer simulation of the system. This is in contrast to the previously mentioned brute-force studies where these are considered fixed. The result of this is that the computer simulation can identify the set of optimal fluid parameters that result in the best performance in a single computer simulation. This set of optimal fluid parameters can then be mapped against a database of existing fluids to identify the fluid that has the properties that are closest to this optimal solution. Ultimately, the development of this model can streamline the selection process for a working fluid and point the system designer towards an optimal fluid without relying on the less efficient brute-force method.

As a caveat, it is worth mentioning that the performance of the system may not be the only factor you need to consider. The selected fluid must also meet a whole host of other criteria including the impact of the fluid on the environment, the fluid’s safety characteristics (i.e., flammability, toxicity, material compatibility) and cost, amongst others. Nonetheless, identifying the characteristics of an optimal fluid remains an important first step for any ORC system.

Results obtained using the method developed within this research. The left image shows the relationship between the temperature of heat source (in the horizontal direction) and the critical temperature of the fluid (in the vertical direction) which is one of the key fluid parameters that determines the fluid behaviour. The right image shows how the results obtained using the new model map onto real fluids.

Acknowledgement

This work was completed as part of the NextORC project, which is funded by the UK Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) [grant number: EP/P009131/1].

More details of this research can be found in the following scientific articles, which were published as open-access articles under the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0).

White, M., Sayma, A., 2019, “Simultaneous cycle optimization and fluid selection for ORC systems accounting for the effect of the operating conditions on turbine efficiency”, Front Energy Res, 7, 50. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenrg.2019.00050

White, M., Sayma, A., 2018, “A generalised assessment of working fluids and radial turbines for non-recuperated subcritical organic Rankine cycles”, Energies, 11(4), 800. https://doi.org/10.3390/en11040800