What is a supercritical carbon dioxide power system?

The end of 2020 brought with it a new publication - a review paper discussing the current state-of-the-art in supercritical carbon dioxide (CO2) technologies for power generation. But to the uninitiated, what is a supercritical CO2 power system? Let’s see if we can cover some basics.

Within the ORC-101 section, we have already introduced the topic of a thermal power system and a working fluid. We have also discussed that common power systems operate with air or water, or possibly an organic fluid, as their working fluid. So, with that in mind, the first thing that we can note is that a supercritical CO2 power system is simply a thermal power system that operates with CO2 as its working fluid.

But what does the term supercritical mean? Well, that is a little bit harder to explain.

The textbook definition of a supercritical fluid is a fluid that is at a temperature and pressure that is greater than the temperature and pressure at its critical point, at which point there is no distinction between liquid and vapour phases - but what does that actually mean?

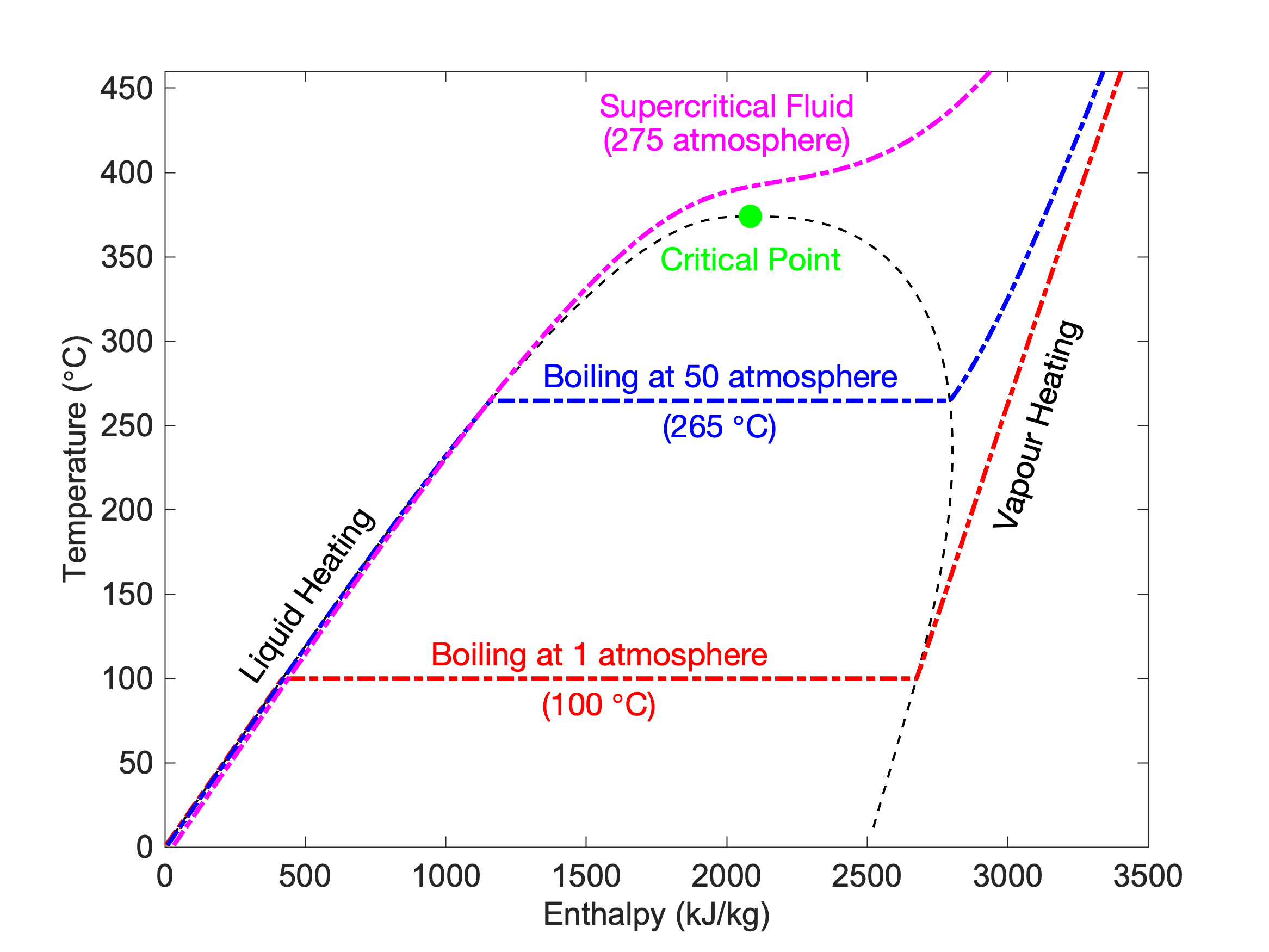

Let’s start by considering water. We know that under atmospheric pressure water boils at 100 degrees Celsius. Moreover, boiling is the process in which water transitions from being in a liquid state (water) to a vapour state (steam), and to obtain that transition a certain amount of energy needs to be added in order to break the bonds that hold the water molecules together and turn it into a steam.

Well, if you were to now put that water in a closed vessel and subject it to a pressure that is double atmospheric pressure, the boiling temperature would increase to around 120 degrees Celsius. And if you were to increase the pressure to 50 times atmospheric pressure, the boiling temperature would increase to around 265 degrees Celsius. But more importantly, as you increase the pressure, the amount of energy required to transition from liquid to vapour reduces.

And if you were to continue increasing the pressure the amount of energy required to obtain that transition reduces and reduces until you reach a point at which no energy is required at all.

At that point there is no longer a discernible difference between the liquid and vapour phases and the fluid is referred to as a supercritical fluid. The point at which that occurs is referred to as the critical point, and for every fluid that is defined by a specific temperature and pressure.

For water, that occurs at 374 degrees Celsius and a pressure or 221 bar (or 218 times atmospheric pressure).

For CO2, that occurs at a temperature 31 degrees Celsius and a pressure of 74 bar (or 73 times atmospheric pressure).

So, in simple terms, a supercritical CO2 power system is particular type of thermal power system operating with CO2 as its working fluid, and within the cycle the CO2 is maintained at a temperature above 31 degrees Celsius and a pressure above 74 bar.

Besides that, the operation of the system, at least in principle, is the same as any other system with the working fluid undergoing compression, heat addition, expansion and heat rejection in order to generate power from an available heat source.

OK, great. But why is that interesting?

Well, that is a great question. Perhaps you might just want to read the review paper to find out…

Heating of water at different pressures, with each coloured line representing a different pressure. At a pressure of 1 atmosphere (red line) water is first heated from 0 degrees Celsius up to 100 degrees Celsius. A certain amount of enthalpy (essentially energy) is required to transition into vapour as shown by the horizontal red line, after which heating of the vapour continues. At a pressure of 50 atmosphere, the amount of energy required to boil the water is reduced, and at 275 atmosphere the pressure is higher than the critical point and there is no distinction between liquid and vapour phases.

Review of supercritical CO2 technologies and systems for power generation

You can check out the full paper here.

Credit to my co-authors from both City, University of London and Brunel University London:

Martin White, Giuseppe Bianchi, Lei Chai, Savvas Tassou, Abdulnaser Sayma

Abstract

Thermal-power cycles operating with supercritical carbon dioxide (sCO2) could have a significant role in future power generation systems with applications including fossil fuel, nuclear power, concentrated-solar power, and waste-heat recovery. The use of sCO2 as a working fluid offers potential benefits including high thermal efficiencies using heat-source temperatures ranging between approximately 350 and 800 degrees Celsius, a simple and compact physical footprint, and good operational flexibility, which could realise lower levelised costs of electricity compared to existing technologies. However, there remain technical challenges to overcome that relate to the design and operation of the turbomachinery components and heat exchangers, material selection considering the high operating temperatures and pressures, in addition to characterising the behaviour of supercritical CO2. Moreover, the sensitivity of the cycle to the ambient conditions, alongside the variable nature of heat availability in target applications, introduce challenges related to the optimal operation and control. The aim of this paper is to provide a review of the current state-of-the-art of sCO2 power generation systems, with a focus on technical and operational issues. Following an overview of the historical background and thermodynamic aspects, emphasis is placed on discussing the current research and development status in the areas of turbomachinery, heat exchangers, materials and control system design, with priority given to experimental prototypes. Developments and current challenges within the key application areas are summarised and future research trends are identified.