An introduction to carbon dioxide blends as working fluids

In my last post I introduced the topic of supercritical carbon power dioxide power cycles. Taking that a step further, this month, as part of the European research project SCARABEUS, our team at City have published a new paper that explores the consequences of CO2-blends on cycle and turbine design. So, what are CO2-blends? And why are they interesting?

Let’s start with the answering the first, and slightly easier, question.

A fluid blend is simply a mixture of two (or possibly more) fluids that are combined together to form a new working fluid. So, a CO2-blend is quite simply a mixture of CO2 combined with another fluid. For the sake of convenience lets define that as an arbitrary fluid called Fluid A.

Now, let’s move onto starting to address the second, and slightly tricker, question.

In my previous post I introduced the topic of subcritical and supercritical conditions and also talked about the critical point. As a reminder, this is the point that distinguishes between subcritical and supercritical conditions, and for every fluid this is defined by a specific temperature and pressure.

So, if we consider our CO2-blend, which is composed of CO2 mixed with Fluid A, we can say that we have a mixture of two fluids, each with their own critical point. However, since the two fluids are combined, we now have a CO2-blend that has its own critical point.

The precise critical point of the CO2-blend will depend on how much Fluid A is added to CO2. For example, if we have a mixture that is composed of 95% CO2 and 5% Fluid A it is relatively easy to rationalise that the behaviour of the blend will be similar to pure CO2. Likewise, if the mixture was composed of 10% CO2 and 90% Fluid A we can rationalise that the behaviour of the mixture will be similar to pure Fluid A. And at 50%/50% it might be somewhere in the middle.

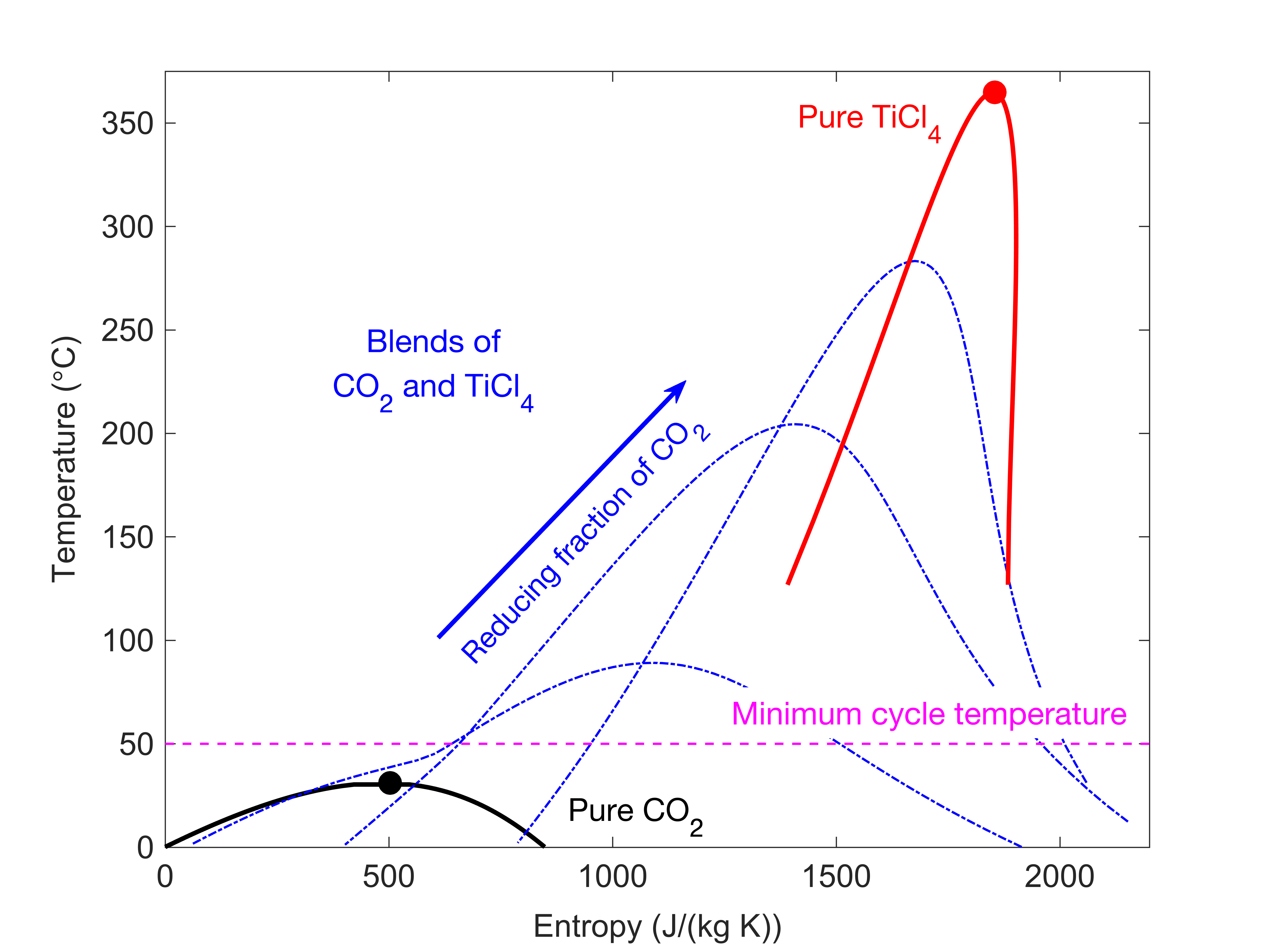

This behaviour can be captured by considering the figure below which corresponds to a CO2-blend composed of CO2 and titanium tetrachloride (TiCl4).

For a particular fluid we can evaluate the location of the critical point (circle markers) by considering the saturation dome of the fluid (black, red and blue lines). If we consider a mixture of CO2 and TiCl4 we can see that as we reduce the amount of CO2 within the CO2-blend we can shift the saturation dome (and critical point) away that of pure CO2 and towards that of pure TiCl4.

So, why are they interesting?

In simple terms, the use of a CO2-blend, instead of pure CO2, introduces the ability to tailor the working fluid to the application and to potentially improve the thermodynamic performance of the cycle.

In the context of this work and the SCARABEUS project, their use could allow efficiency improvements in concentrated-solar power plants. This is achieved by raising the critical temperature of the fluid above the minimum cycle temperature and allowing condensation within the cycle.

Interested in understanding a bit more about the implications of using CO2-blends on cycle design, and also on the design of the turbine for these systems? Then I encourage you to check out our new paper below.

Paper details

Sensitivity of transcritical cycle and turbine design to dopant fraction in CO2-based working fluids

You can check out the full paper here.

Abstract

Supercritical CO2 (sCO2) power cycles have gained prominence for their expected excellent performance and compactness. Among their benefits, they may potentially reduce the cost of Concentrated Solar Power (CSP) plants. Because the critical temperature of CO2 is close to ambient temperatures in areas with good solar irradiation, dry cooling may penalise the efficiency of sCO2 power cycles in CSP plants. Recent research has investigated doping CO2 with different materials to increase its critical temperature, enhance its thermodynamic cycle performance, and adapt it to dry cooling in arid climates.

This paper investigates the use of CO2 /TiCl4, CO2 /NOD (an unnamed Non-Organic Dopant), and CO2 /C6 F6 mixtures as working fluids in a transcritical Rankine cycle implemented in a 100 MWe power plant. Specific focus is given to the effect of dopant type and fraction on optimal cycle operating conditions and on key parameters that influence the expansion process. Thermodynamic modelling of a simple recuperated cycle is employed to identify the optimal turbine pressure ratio and recuperator effectiveness that achieve the highest cycle efficiency for each assumed dopant molar fraction. A turbine design model is then used to define the turbine geometry based on optimal cycle conditions.

It was found that doping CO2 with any of the three dopants (TiCl4, NOD, or C6 F6) increases the cycle’s thermal efficiency. The greatest increase in efficiency is achieved with TiCl4 (up to 49.5%). The specific work, on the other hand, decreases with TiCl4 and C6 F6, but increases with NOD. Moreover, unlike the other two dopants, NOD does not alleviate recuperator irreversibility. In terms of turbine design sensitivity, the addition of any of the three dopants increases the pressure ratio, temperature ratio, and expansion ratios across the turbine. The fluid’s density at turbine inlet increases with all dopants as well. Conversely, the speed of sound at turbine inlet decreases with all dopants, yet higher Mach numbers are expected in CO2 /C6 F6 turbines.

Acknowledgement

This work has been conducted as part of the SCARABEUS project. The SCARABEUS project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No. 814985.